You just finished the tenth rep of five military press sets, packing on an extra twenty pounds to test your muscle strength, when you hear a slight popping sound, and instant twinge of pain. Must be my rotator, you worry, rubbing your aching shoulder joint.

Or maybe you are a fitness freak. Lunges, sit-ups, push-ups, belly busters, you name it, you do it. One day, you wake-up with a pain at the base of your back and you know something just isn’t right. Did I blow out my L5, you ask yourself.

You worry how long you will be on the shelf and what the potential time away from your daily regime will mean for your work-out. All that effort, all that energy, wasted, you think, you’ll have to start back to square one.

Not necessarily, claim physicians and scientists in the know.

You might have heard the claims before that your muscles have memories gained from the repetitive motion of an action, say, performing a military press, and, even after extended breaks, the muscle group will bounce back. In some cases, muscle memory proponents argue, a short break or even extended period away from the activity, will help you perform even better than you had prior to your time off.

Not a believer in “muscle memory?” Now there is hard science to back-up the claims of fitness gurus and trainers who swear by the theory of muscle memory.

The Science of Muscle Memory

On August 16, 2010, as reported in Iron Magazine and Wired Science, researchers at the University of Oslo in Norway presented a report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences examining the science of how muscles retain a form of memory.

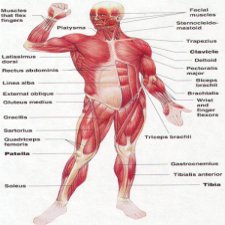

Muscle cells are huge and past research has shown that they have the potential to grow even larger with regular exercise melding with a stem cell found inside the muscle fiber itself. Kristian Gunderson, leader of the Oslo research group, in presenting the muscle research, explained that the memory is stored in the muscle’s DNA.

Previously, Gunderson explained, researchers thought when muscles atrophied from lack of use or exercise that the DNA stored in the muscle’s nuclei would become lost. The muscle would “forget” how to operate and the patient or athlete would lose his or her strength, agility, or level of fitness previously achieved.

The “forgetting” was termed apoptosis, a sort of cell death march. The new report, though, demonstrates that the extra nuclei, in fact, are not lost, enabling a muscle to regain its former shape after retraining.

According to Wired Science, “Gundersen’s team simulated the effect of working out by making a muscle that helps lift the toes work harder in mice. As the muscle worked, the number of nuclei increased, starting on day six. Over the course of 21 days, the hard-working muscle increased the number of nuclei in each fiber cell by about 54 percent. Starting on day nine, the muscle cells also started to plump up, adding an extra 35 percent to their volume.”

The results indicate that, over the course of time and through hard work, the body’s muscles can add nuclei needed to gain muscle mass.

The Oslo research team tested their “muscle memory” theory by severing the mice’s nerves leading to the bulked-up muscles so atrophy would occur. Indeed, as the muscles became atrophied, the cells within decreased by about 60% yet the amount of nuclei embedded in muscles remained unchanged.

Why Is that Important?

While apoptosis – cell death – did settle-in to the atrophied muscles, the muscle fibers themselves remained undamaged. According to Gunderson, the muscle nuclei could stay intact up to three months in a mouse’s body, with wide ranging implications for humans.

“I don’t know if it lasts forever,” Gunderson said in his report, “but it seems to be a very long-lasting effect.

“Since the extra nuclei don’t die, they could be poised to make muscle proteins again, providing a type of muscle memory.”

The report resonated with some in the scientific community such as Bengt Saltin, a muscle physiologist from the University of Copenhagen who called the study, “fascinating thinking,” while Lawrence Schwartz, from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, remarked that, “their data just feels right.”

What Does This Mean for Your Workout?

The research gives hope to you weekend warriors who tweak a muscle group and must take a break, or to an athlete that is severely injured and placed on the shelf for several months. The muscle, if already fit, can rebound when workouts resume.

In fact, argues Dr. Kristie Leong from the Medical College of Virginia, a break from training may even help the effectiveness of your work-out. Leong contents that “muscle memory,” in some cases, holds you back, especially in resistance training, where you can reach a certain plateau where you stop seeing gains unless you “challenge yourself by lifting heavier weights or doing different exercises.” The muscles have learned your routine, and thus, the activities lose some of their former impact.

“Taking a week or two away from strength training shouldn’t set you back,” says Dr. Leong. “In fact, if you’ve reached a plateau, it may boost muscle growth and give you more definition in the long run. Muscle memory can work against you by causing plateaus, but it’s a definite advantage if you need to stop working out for a while. Learn how to use it to your advantage.”

So, don’t fret the time off if you are hurt or if you are too busy for a workout. Since you have invested your energy and effort into building-up your muscles, through all of your fitness routines and efforts, your muscles will rebound quickly and perhaps reach even greater heights.

The Oslo results, if proven correct, may also have long reaching implications for youth fitness programs and healthy living. Muscle mass, it has been proven, does not last forever. As we age, we lose muscle, but, if the nuclei in our muscles have been increased due to a healthy lifestyle of working-out in our younger years, the atrophy becomes less, raising our quality-of-life as we get older.

This is especially vital in our formative and teen years. It has been well-documented that childhood obesity is an epidemic in this country and, even those children who do not over-eat, tend to spend more of their time behind a monitor playing video games or online chatting with friend way more than they do engaging in physical activities.

Fitness initiatives from the federal government, and sports leagues such as the NBA and NFL , have helped raise awareness in the schools and in homes around the nation. However, without a cultural change in thinking, attitude, and action, those young kids who spend hours using their thumb muscles could comprise a new generation of unhealthy and unfit senior citizens.