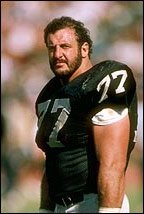

“If me and King Kong went into an alley, only one of us would come out, and it wouldn’t be the f*cking monkey.”

“If me and King Kong went into an alley, only one of us would come out, and it wouldn’t be the f*cking monkey.”

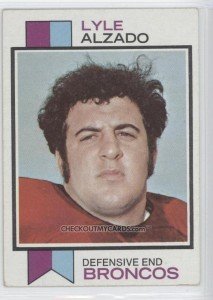

–Lyle Alzado, NFL lineman, circa 1980s

Steve Courson strode into the Pittsburgh neighborhood drugstore, looking huge and menacing in gym shorts and tank top. Other customers gawked at Courson’s massiveness, the muscles bulging on muscles–He’s a Steeler, they assured each other, noting the Super Bowl rings–but he paid them no mind. Though gentlemanly, respectful of people, Courson was in no mood for pleasantries or even eye contact; it was the NFL offseason, 1982, and he had come to the pharmacy to purchase anabolic steroids. No steroid prescription was required, not for Steelers at this drugstore. Courson quietly scanned the inventory, reading labels on plastic bottles and vials, asking nothing of the compliant pharmacist hovering nearby. This football player needed no advice about juicin’. He knew exactly what he wanted, ordering plenty of steroids for himself, his O-line teammates, and his power-lifting friends.

Into the shopping bag went Dianabol, Anavar, and Anadrol in pill form, and for injectables, Deca-Durabolin, Winstrol Depot, and the testosterone esters cypionate and propionate. Courson picked out other compounds, human chorionic gonadotropin to stimulate testosterone production, anti-estrogens to counter side effects of cycling on anabolic androgens; he then finished with a box of hypodermic needle-syringes. Courson wrote a personal check for the total amount, grabbed up the bulging bag, and walked out.

For football fans around that pharmacy, the NFL’s ever-growing problem with muscle doping in the 1980s was as apparent as Courson’s physique. Fans, however, ignored what this scene really meant. They just admired a young athlete and his sport.

Decades later, a middle-aged Steve Courson shook his head at the thought. “Can you imagine the sight of me back in those days, about 285 all ripped-out, coming out of the pharmacy? I’d walk out with a shopping bag full [of steroids],” he said. “Nowadays, people would be like, ‘What are you doing?’ Back then, nobody had a clue.”

At the time, Courson and other Steelers were immersed in off-season weightlifting and, like a multitude of NFL players representing every team, cycling on anabolic steroids. They were preparing for the coming season, but pros like Courson would also enter a made-for-TV event dominated by the Steelers, the strongest-man competition for NFL players.

Moreover, Courson was amid a chemical breakthrough, perfecting his acquired science of “stacking” steroids in combinations for maximum muscle-building. In eight years since college football, Courson had cycled a half-dozen times, never in-season nor more than once annually, and always at or near therapeutic dosage levels. “The first year I competed in the strongest-man competition [1981], I cycled on D-bol and Deca; it was really light,” he recalled. “The following year, ’82, was the first year I hiked it up pretty good.”

Courson mixed testosterones with potent anabolics such as Winstrol and Anavar, concocting a special tissue-pumping synergy. Consuming pills and taking injections like never before, he experienced abdominal cramps and increased irritability, but the performance enhancement paid immediate dividends for his particular job: Courson added about 15 pounds in lean body mass and his strength shot up. When bench-pressing 405 pounds, Courson increased from 6 repetitions to an astounding 14. “That taught me. I learned something there,” Courson said of the accelerated cycling. “That’s when I definitely knew that no matter what I did training-wise, there was nothing that I could do to compare to this. I was totally sold. There was just no way to train to match that.”

Players everywhere were figuring it out, including at colleges and high schools. Any period of “isolated” steroid use in higher competitive football was over, if that had ever held longer than briefly at any level. The chemical-arms race was on, thoroughly covering leagues from the colleges to the pros, and hitting hard at high schools. Many users had advanced beyond cowboy chemistry. In the NFL, steroid sophisticates like Courson were becoming common. “They were on many [teams],” he recalled. “At the time, the early ’80s, I was savvy… I knew the game. I understood it. I read about it. I wouldn’t just pop needles into my butt without thinking.”

Players everywhere were figuring it out, including at colleges and high schools. Any period of “isolated” steroid use in higher competitive football was over, if that had ever held longer than briefly at any level. The chemical-arms race was on, thoroughly covering leagues from the colleges to the pros, and hitting hard at high schools. Many users had advanced beyond cowboy chemistry. In the NFL, steroid sophisticates like Courson were becoming common. “They were on many [teams],” he recalled. “At the time, the early ’80s, I was savvy… I knew the game. I understood it. I read about it. I wouldn’t just pop needles into my butt without thinking.”

In his 1991 autobiography False Glory, Courson declared “unequivocally” that 75 percent of his offensive line mates in Pittsburgh used anabolic steroids at least once. Courson, a Steeler from 1977 to 1984, named no names, but other reports were confirming use among period Pittsburgh linemen such as Jim Clack, Mike Webster, Rick Donalley, and Terry Long, while implicating others. Steelers running back Rocky Bleier acknowledged he used anabolic steroids.

Rival NFL players called Pittsburgh the “Steroid Team,” but league-wide abuse rendered that charge hypocritical. Every season in Dallas, for example, the Cowboys’ Super Bowl hopes relied not so much on the skills of Coach Tom Landry as on numerous drug-using players, from “yoking-up” linemen to “dabbler” backfield players. Landry’s strength program had a confirmed steroid user as a coach, and at least one of his juicing players was bound for Canton, the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Decades later, media and politicians fretted, rather fashionably, over muscle doping’s effects on records in baseball—after winning in pro football was affected through the TV age. “It was everywhere,” Courson said in 2005. “Back then (the 1980s), it was so wide open. That’s why for people to deny it was out there, you had to live in a bubble.”

Offensive linemen were not the only culprits. Defensive stars of the period who would acknowledge using anabolic steroids included Bills linebacker Jim Haslett and Cowboys safety Charlie Waters, along with linemen Joe Klecko and Mark Gastineau of the Jets, Randy White and John Dutton of the Cowboys, Steve McMichael of the Bears, and Lyle Alzado, who played for the Broncos, Browns, and Raiders.

Klecko discussed steroids for the 1989 book Nose to Nose, which he co-authored with former Jets teammate Joe Fields and sportswriter Greg Logan. Klecko estimated a large majority of offensive and defensive linemen used steroids, and he believed the training method “became commonplace in the NFL in the late seventies and increased during the next decade to the point where it became a major health issue,” the book stated. Klecko added, “I can’t prove it, but based on my experience, I’d say there were a high number of steroid users.”

Many more NFL insiders of the time corroborated Courson and Klecko about steroid prevalence, collectively portraying that a significant amount of players used, if not a majority.

There existed no steroid policy. The league, franchises, union, and players had done nothing to curb anabolic steroids’ spread in the game, since the drugs’ arrival in the early 1960s. Management, in fact, had long publicly purported that performance-enhancing drugs were under control in the league, a problem of the past, and were not proven to work. “Amphetamine and steroid use in the NFL is said to be down dramatically from the early ’70s. This was due in large part to game films, players seeing that they actually were being hindered rather than helped by drugs in games,” Washington Post sports columnist Ken Denlinger reported inaccurately in July 1982, as monsters like Courson and Klecko headed to training camps.

In reality, NFL players relied heavily on performance enhancers, especially steroids, painkillers, “speed,” and more so than ever before, whether or not writers and fans could believe it. “I don’t regret anything I’ve done as far as pharmaceutical use is concerned,” Courson told Sports Illustrated in 1985. “It’s very easy for people on the outside to criticize. But it’s different when it’s your livelihood, when it’s your job to keep a genetic mutation from getting into your backfield.”

The jungle was only getting deeper for survival of the fittest in football. The anabolic era was flying out of control, forever perhaps, and many players were preparing themselves, becoming equipped, to whip King Kong.

References:

Alzado, L. (1991, July 8). ‘I’m sick and I’m scared.’ Sports Illustrated, p. 20.

Bayless, S. (1990). God’s Coach. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Blount, R., Jr. (1974). About Three Bricks Shy of a Load. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Bouchette, E. (1985, May 15). I used steroids, Bleier says. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, p. 21.

Cobb, C. (1993, May 24). Mike Webster medical report. Hematology-Oncology Medical Associates, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA.

Courson, S. (2005, March 7). Interview with author. Farmington, PA.

Courson, S. (2005, May 1). Telephone interview with author.

Courson, S. (2005, June 22). Telephone interview with author.

Courson, S., & Schreiber, L.R. (1991). False Glory. Stamford, CT: Longmeadow Press.

Denlinger, K. (1982, July 2). Teamwork is the solution. Washington Post, p. C1.

Fisher, M. (2005, July 10). Waters, Steroids and a Slippery Slope. TheRanchReport.com/Scout.com.

Garber, G. (2002, January 6). Outside The Lines: Mark Gastineau and Bootleg Souvenirs. ESPN.com [Online].

Johnson, W.O. (1985, May 13). Steroids: A Problem of Huge Dimensions. Sports Illustrated, p. 38.

Johnson, W.O., Lieber, J., & Keteyian, A. (1985, May 13). Getting Physical—and Chemical. Sports Illustrated, p. 50.

Johnson, W.O., Lieber, J., & Keteyian, A. (1985, May 13). A Business Built on Bulk. Sports Illustrated, p. 56.

Huizenga, R. (1994). “You’re okay, it’s just a bruise”. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Klecko, J., Fields, J., & Logan, G. (1989). Nose to Nose. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Long Positive. (1991, July 25). Steelers’ Long Tests Positive for Steroids. United Press International [Online].

Morrissey, R. (1995, January 10). Drug Suspicions Still Dog Football. Rocky Mountain News, p. 17B.

Provost, W. (1983, September 11). Study of All-American Provides an NU Shock. Omaha World-Herald [Online].